Siiri Pohjolainen: Kyyneleet

Näyttelyn avajaiset perjantaina 1.11. klo 18-20. Vapaa pääsy, tervetuloa!

Siiri Pohjolaisen suurikokoisissa teoksissa valuu maalia ja vettä, tipahtelee kyyneleitä.

Muodoltaan kyyneleet ovat tiiviitä ja kolmiulotteisia nestepisaroita, sinisiä kuin taivaan heijastus järvivedessä. Vesi on osa Pohjolaisen maalauksia – se ohentaa katosta riippuvien kankaiden väriä ja tuntuu tekevän siitä lähes mattamaisen karheaa. Kun pisarat putoavat vesiliukoisesta maalista syntyvälle väripinnalle, ne virtaavat kankaalle sen pinnanmuotojen mukaan. Kyyneleen muotoon ommellut riippuvat punaiset pisarat puhkovat kuin avohaavoja tilaan. Teoksia raidoittavat punavärin kaikki sävyt oranssista viininpunaiseen, ja kuiva ruskea rapisee ruosteena pisaran kaarevaan pintaan.

Kyynel on taiteen historiassa voimakas aihe ja merkki tunteesta – ilosta, surusta, yllätyksestä, vihasta. Renessanssin aikaan Giotto maalasi ensimmäisten joukossa kasvoja pitkin valuvia kyyneleitä kuten Padovan Scrovegnin kappelin Pyhät viattomat -freskossa (1304–1305). Kyyneleiden ilmestyminen muutti osaltaan taiteen kehitystä, sillä perinteisen uskonnollisten aiheiden kuvitusten sijaan teokset alkoivat lähetä elävän ihmisen maailmaa näyttämällä hänen tunteensa kuvatuissa hahmoissa. Myöhemmin kyyneleet valuivat Sir John Everett Millais’n hukkuvan Ofelian (1851–1852) kasvoilla, ja ne tahrivat tyynyliinan Tracey Eminin My Bed -installaatiossa (1998).

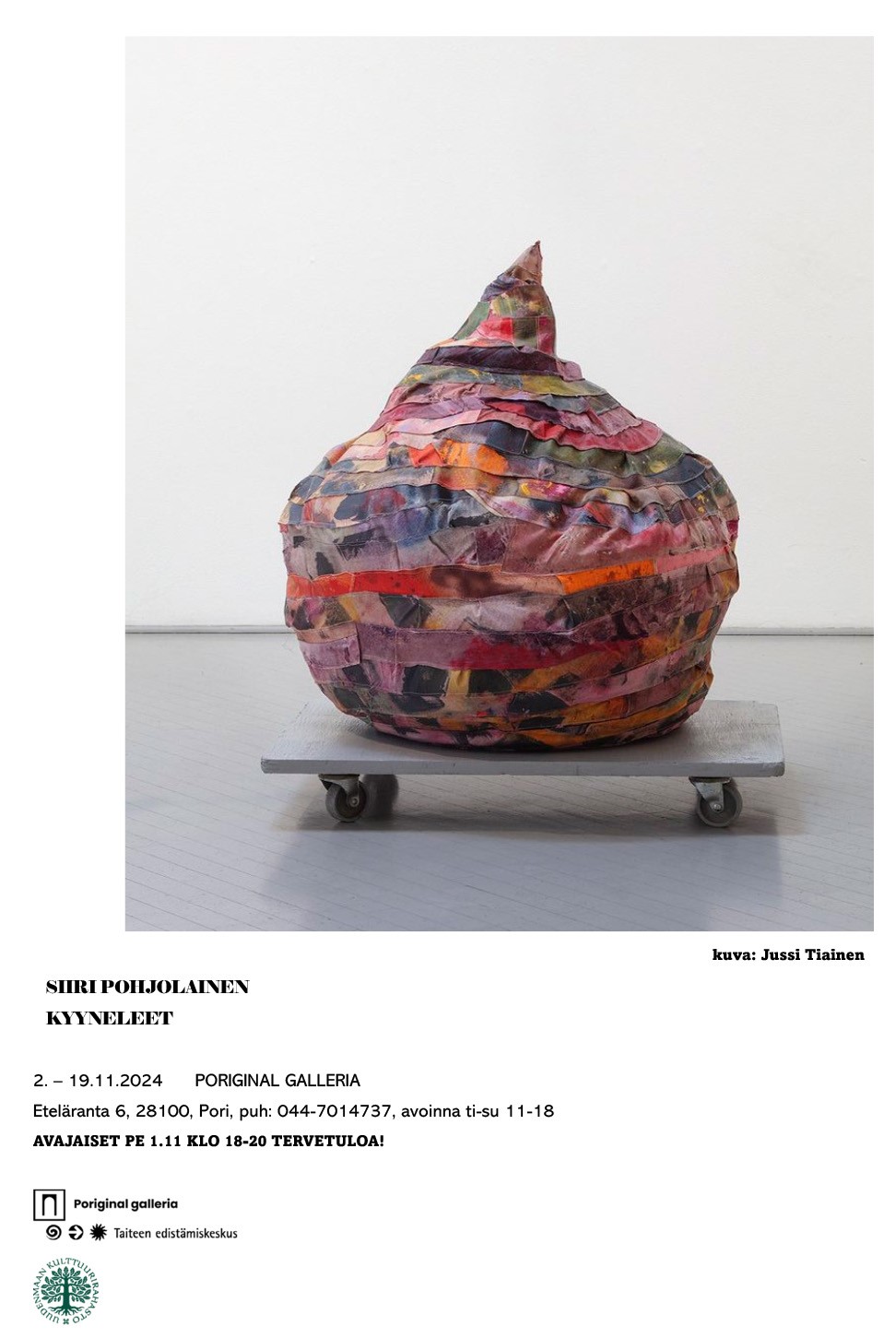

Pohjolaisen tekniikkana on akryylimaali, öljypastelliliitu ja kollaasi kankaalle. Sen pinnassa värit vaihtuvat sävyjen logiikan mukaan. Mittakaava ja värin käsittely vievät ajatukset 1970–1980-lukujen uusekspressionismin voimakkaaseen maalauksellisuuteen ja abstraktin ja esittävän eron ylittymiseen. Värin lisäksi myös kangasmateriaali kerrostuu kollaasien tapaan: suurissa teoksissa on runsaasti mittaa jo alussa, mutta kun ainesta tarvitaan syvyyssuunnassa lisää, taiteilija leikkaa ja ompelee maalattuja kankaita yhteen. Kangaskerrosten kasautuessa syntyy joko kaksiulotteisia maalauksia tai kolmiulotteisia veistosmaisia installaatioita.

Mattapintaiset öljypastellit tuottavat vaihtelua maalattujen pintojen intensiteettiin. Pastellien läpinäkymättömyys on sukua kankaisiin applikoiduille mokkanahalle – se saa katsojan ehkä toivomaan mahdollisuutta koskettaa ja kuvitella pastelliväreille yhtäläinen tuntu. Sormet haluavat nähdä, katsominen on koskettamista.

Galleriatilassa kävijään eivät vetoa vain kyyneleet, vaan teosten dramaattisesta ripustuksesta syntyy samalla näyttämön kaltainen tila, värillinen teatteri. Astuessaan taustakankaiden keskelle katsoja joutuu omaksumaan suhteen teoksiin ilman, että niistä on mahdollista täysin etääntyä. On kuin kaksipuoleiset kankaat toimisivat näyttämön tapahtumien taustana, kun taas näyttelijöinä esiintyvät maalauksista syntyneet veistokset, kiteytyneet pisarat.

Katsomisen suunta on kävijän valittavissa, vain yhtä näkökulmaa ei Pohjolaisen teoskokonaisuudelle ole.

Martta Heikkilä, FT, dos.

EN

Siiri Pohjolainen: Tears

Siiri Pohjolainen’s large canvases drip paint and water, they shed tears. Tears, compactly shapered three-dimensional droplets, are blue like a reflection of the sky on a lake. Water is an indistinguishable part of Pohjolainen’s paintings – it dilutes the paint used in the canvases hanging from the ceiling and makes their surface matte and rugged. When drops fall on the plane of water-soluble paint, they seem to flow according to the shapes of the canvas. Moreover, tears lend their shape to some of the paintings that have been sewn to form drop-like red sculptures that punch open wounds in the space. Shades of red, ranging from orange to burgundy, tone the curving shape of the drops. In some parts, they turn the dry, brown tones into rust.

Tears are a powerful subject in the history of art – signs of emotion joy, sadness, surprise andanger. At the time of the Renaissance, Giotto was among the first to paint tears flowing on the depicted face, as in the fresco The Massacre of the Innocents (1304–1305) in Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. The appearance of tears contributed to a change in the development of art, as instead of illustrations of rigid religious subjects, artworks began to reflect the world of humans by showing their emotions. Since then, tears have poured down the face of Sir John Everett Millais’ drowning Ophelia (1851–1852) and stained the pillowcase in Tracey Emin’s My Bed installation (1998).

Pohjolainen works with acrylic paint, oil pastels and collage on canvas. There, colours changeaccording to the logic of shades. The scale of the paintings and treatment of colour remind us of the strong painterly character of neo-expressionist painting of the 1970s and 1980s, in which the difference between the figurative and the abstract was no longer significant. Pohjolainen not only adds layers of paint, but she also cuts, folds and superposes canvas to form collages. The scale of the works is abundant from the beginning, but it grows into new dimensions of depth wherever more pieces of canvas are sewn together. The cumulation of layers creates either two-dimensional paintings or three-dimensional sculptural installations. Not only paint, but also the matte finish of oil pastels produce variation in the intensity of the surfaces. The opaqueness of pastels is related to the sensory quality of the scraps of suede applied to canvases. Their leathery surface will perhaps make the viewer wish to touch it and imagine an equal feel for pastel colors. Our fingers want to see, looking means touching.

In the gallery space, the visitor is attracted not only by the latent emotion hidden in the tears, but also by the dramatic installation of the works. It transforms the space into a stage or a colored theatre. In the middle of the background canvases, the viewer must relate with the works without reserve, not being able to contemplate the scene at a distance that would separate him or her from them. It is almost as if the double-sided canvases serve as a backdrop for the events taking place on the stage, where sculptures, crystallised teardrops, work as actors. The spectator’s task is to navigate between the scenes that arise from Pohjolainen’s works that offer multiple angles and aspects for viewing.

Martta Heikkilä, PhD